As blockchain ecosystems and decentralized solutions continue to evolve and gain traction, decentralized governance is also gaining traction and being explored in a variety of ways as a methodology among other decision-making frameworks.

However, a series of governance incidents with negative consequences, such as hacks, sybil attacks, and property rights violations, etc. have amply demonstrated that current governance frameworks are highly vulnerable to risks and need to evolve into more advanced forms.

To this end, we can consider four pillars for framing decentralized governance based on the essence of decentralization.

The blockchain industry is generous with the prefix ‘Decentralized’ - and governance is no exception. Decentralized governance seems to be all about giving network participants unlimited autonomy and responsibility, adding flexibility to the organization's decision-making process and ensuring the utility of each in the name of the community.

However, according to Crowd Psychology by Gustave Le Bon, when individuals are granted a lot of rights (or autonomy), they form chaotic and irrational crowds, which are more likely to prioritize emotional decision-making over rational decision-making - in fact, we have directly or indirectly observed in the blockchain ecosystem that decentralized governance can lead to various serious problems if the framework is not set up well.

Then, why do we think decentralized governance is necessary, and if so, what factors can we consider to frame it?

Before we get to the questions, we need to think about the essence of what ‘decentralized’ means. In fact, despite the fact that the concept of decentralization is held up as a virtue by many people inside and outside the industry, there is not yet a single clearly defined sentence about the concept of decentralization, which means that the word is still very abstract and spectral.

One of the biggest concerns with this is that it can lead to a blind pursuit of decentralization or the various properties we expect from decentralized systems (e.g., transparency, immutability, security, censorship resistance, etc.), misrepresenting decentralization as an perfect anti-thesis to centralization, and failing to embrace different attempts in the blockchain ecosystem with rigid bars. Therefore, we need to further reflect on the essence of decentralization by looking at the process of decentralization being achieved, rather than making a limited interpretation of decentralization through outwardly observed phenomena.

Blockchains are not inherently designed for decentralization itself. Rather, it's more accurate to say that it is designed for a transparent, public, trustless P2P network. And 'decentralized’ gets its name from the fact that the way these systems are built is by consensus of the various participants - if you look at the structure of the various blockchains that have emerged to date, there are only differences in the trade-offs of how many participants to accept and the degree of trust to sacrifice, but in the end, they all have in common the same essence of onboarding an unspecified number of participants and introducing consensus and incentive mechanisms to ensure that they are able to confirm unique and identical data in order to continue to operate the trustless system. In short, the essence of decentralization, as a methodology for achieving specific goals, is to create an environment that ensures diverse participation and a framework that can sustain a trustless system.

In the same vein, if we define governance as ‘a decision-making tool for achieving an organization's purpose’, decentralized governance can be defined as ‘a decision-making tool that encourages the active participation of diverse participants and allows them to continue to engage for the organization's purpose in a trusted framework’.

So the next question might be - is it even necessary to insist on decentralized governance while engaging a wide range of participants?

There are millions of different types of governance in the world, so there is no right or wrong way to think about a good governance framework. In other words, decentralized governance is just one framework among many, and the flip side of this is that it can be a good methodology in certain areas.

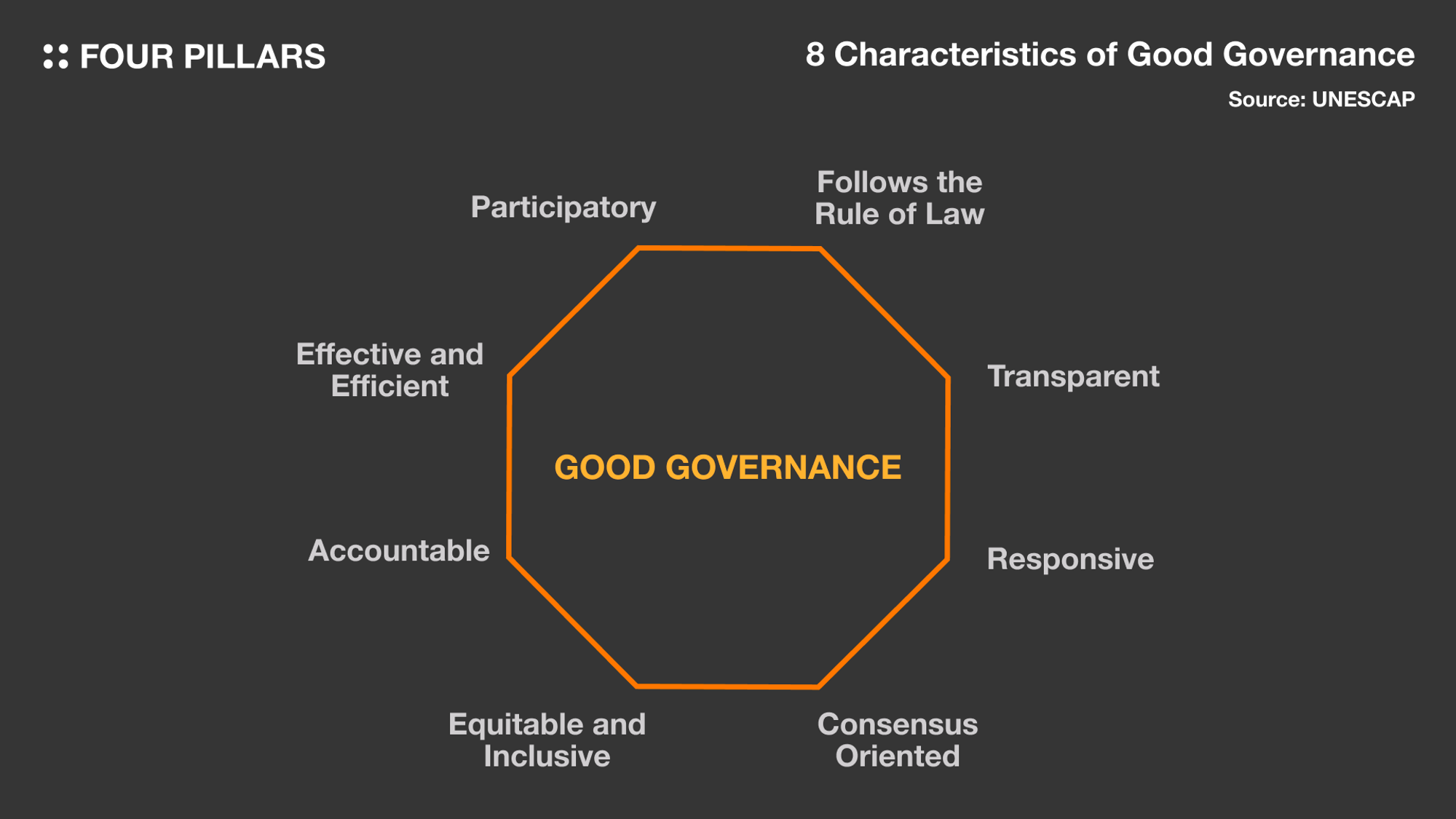

The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) report identifies eight principles to consider in creating a governance framework that is effective in achieving an organization's objectives as follows :

While implementation will vary, it seems likely that decentralized governance can reinforce most of the eight principles above. For example, it can strengthen existing governance structures in the following ways - since all decision-making processes are public, participants can have the same understanding of the problem and decisions can be more acceptable. Furthermore, the more diverse the participants, the more the protocol can achieve credible neutrality and maximize social capital as it focuses on the public good for the whole. If the rules or agendas are well-implemented as automated smart contracts, they can be enforced in a timely and strict manner, creating a sense of discipline in the network.

However, this is the scenario when the decentralized governance framework is ideally set up: many people need to be active and behave correctly, and the system should reflect the distinct characteristics of the blockchain well. The reality is that the blockchain ecosystem still suffers from a number of challenges, including the lack of a technical infrastructure that can transparently track all decision-making processes, support for flexible and effective voting mechanisms to reflect the diverse voices of participants, and a lack of active participation by participants in governance itself. Rather, the series of governance incidents that have severely damaged protocols, including hacks, sybil attacks, and property rights violations, do not bode well for an optimistic future for decentralized governance, but rather amply highlight the fact that current governance frameworks are highly vulnerable to abuse and need to evolve into more advanced forms.

Therefore, in order to help protocols that want to strengthen their governance frameworks to be more decentralized, as well as effective in achieving their goals in the future, we need to discuss the minimum elements that must be considered when designing such frameworks.

Decentralized governance is essentially a space where key issues are discussed in determining the direction of the protocol, so it is important to define the right participants for governance and create an environment where they can have a uniform understanding of the proposed agendas. In addition, it should ensure equitable and accessible engagement of participants for stable and continuous operation, and should not be of a nature that results in biased outcomes for any particular entity(i.e., not neutral).

Most fundamentally, it is important that the protocol defines the scope of the governance agenda according to its purpose and identifies participants with the required expertise.

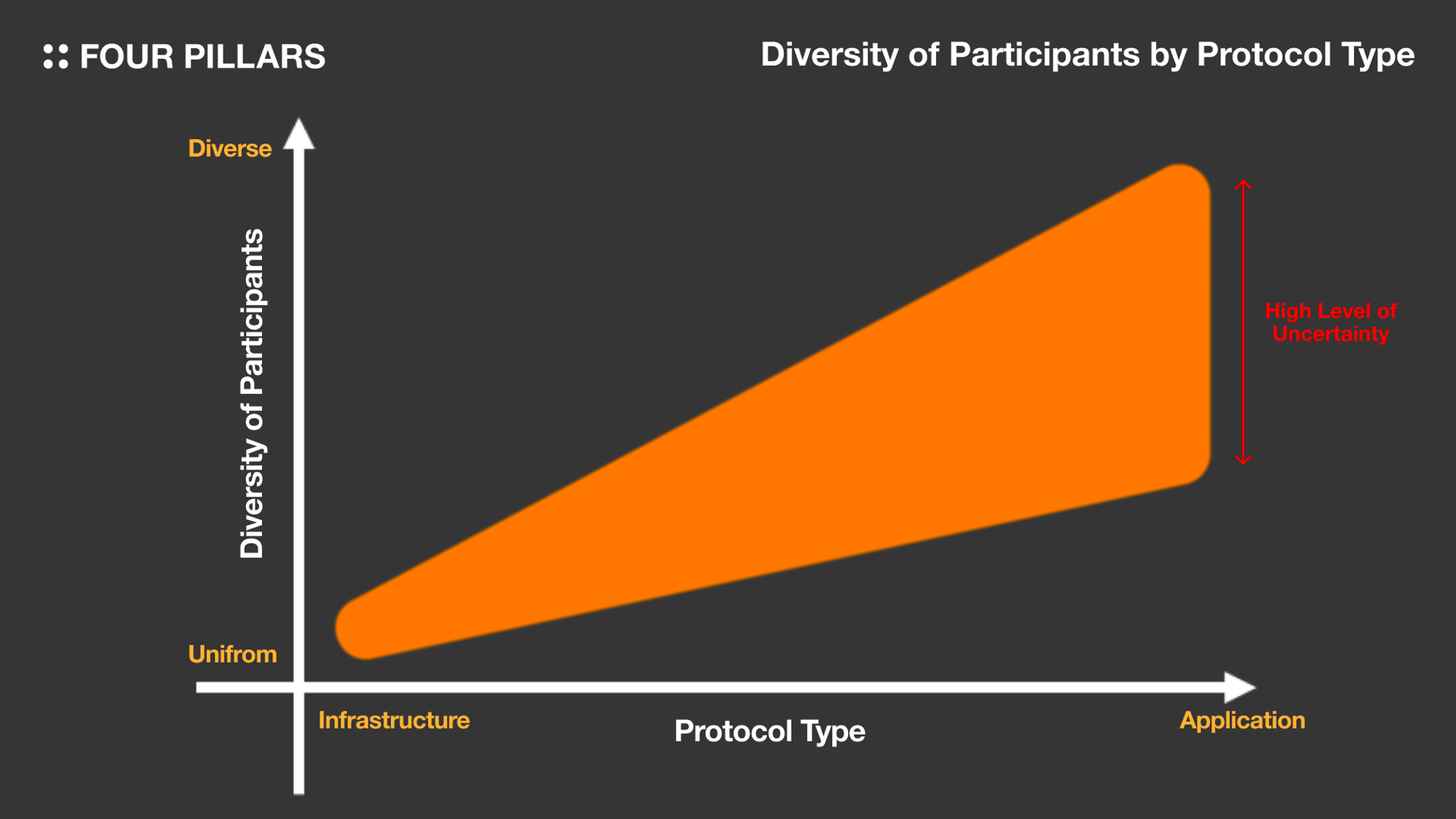

In practice, governance agendas in blockchain ecosystems is very broad, ranging from setting communication standards at the underlying network layer to issues to increase the utility of the service for the end users at application layer.

For protocols that are closer to the infrastructure, the agenda often consists of standards that relate to the technical operation or define immutable properties of the network. Therefore, the actors involved in governance need to have a clear understanding of the vision of the protocol and the history of all the related proposals, as well as technical expertise in network communications and other infrastructure.

Not only are there not many participants that can fulfill all of these requirements, but the relative importance or continuity of each agenda requires a flexible and close communication system between participants. As a result, many mainnets are now adopting off-chain governance to enable flexible communication, and governance minimization to gradually reduce the scope of agendas to make the network more stable and achieve credible neutrality.

However, the closer to the application the protocol is, the more likely it is that the participants will be more heterogeneous and diverse, so the agendas for protocol governance are mostly related to the use or utility of the service in general, or even away from edge cases.

In some cases, especially for less important agendas, token-based on-chain governance may be used, while in other cases, where the scope of the governance is broad, it may be broken down and recursively organized into various DAOs or committees and staffed with specialized personnel.

In short, the protocol should appropriately set the scope of governance based on the type of itself, and recognize the persona of the governance participants it expects. If protocol sets the scope too broadly and leave governance entirely up to the whole participants without appropriate actions, there is a risk that participants may not fully understand the individual proposals, resulting in invalid voting results or deadlocks where no conclusion is reached.

As we've seen in the previous chapter, efficient and effective operation on governance requires the right set of its scope and participants. However, hoping for their voluntary participation without any mechanisms in place can be a bit of a wishful thinking, and relying on this can lead to a more unstable governance system.

Therefore, protocols can consider introducing a variety of incentives to actually attract participants to governance.

(Token-Based) Economic Incentive

First of all, the introduction of economic incentives for participation, which is also the means by which blockchains are technically operationalized, is one of the most effective ways to bring together diverse participants in a short period of time. However, it is important to note that the reason this can work is that, similar to the design of game theory, the scope of the work required is limited so that the criteria for contribution (e.g., running a stable node) and punishment for malicious behavior (e.g., slashing) can be clearly established.

In the case of governance, on the other hand, the range of proposed agendas is likely to be variable. Furthermore, all discussions are qualitative and subjective, making it difficult to establish clear criteria for contribution or punishment. Therefore, if economic incentives are haphazardly introduced for governance behavior without compensating for these limitations, there is a risk that short-term gain-seekers will be mixed in with the group of governance participants, resulting in different degrees of consensus orientation for the protocol within the community - of course, the governance of protocols that are closer to the application may not require a long-term vision alignment between the participants and the protocol, but there is another risk that various conflicts of interest among the participants may develop. Furthermore, if the rewards are easy to liquidate, the risk of plutocracy and sybil attacks may increase, and if they are embedded with various functions, such as native tokens, the security of the network itself may be significantly affected.

In short, if protocols introduce economic incentives such as tokens, they will need to balance the tradeoff between the ease of entry of participants and the risk of potential disruption in the governance space, given the pre-defined scope of governance.

On the other hand, it is worth noting that there are also attempts to create devices that allow users to delegate their voting rights to entities that they believe are best able to represent their interests, or to grant more governance rights in proportion to the length of the token lockup period, such as Curve Finance's Voting Escrow Model. However, while the former allows for more valid voting results and thus more effective governance, it may not completely eliminate the risk of plutocracy, and the latter may be effective in forcing incentive alignment between the protocol and participants during the lockup period, it may not be the best option as it is not clear that participants really fit the governance participant persona that the protocol requires.

(Reputation-Based) non-Economic Incentive

In his hierarchy of needs theory, American psychologist Maslow argued that feeling respected by others can be another motivator for social activity, and many studies have reported a strong correlation between reputation and organizational performance - an example within the blockchain ecosystem is Ethereum's EIP.

Ethereum's governance framework, the EIP, takes an off-chain governance approach that doesn't explicitly reward governance participants financially. Nevertheless, nearly 800 participants have submitted proposals to the EIP and thousands of community members have discussed them, making the EIP a trendsetting blockchain standard. The Ethereum community's active participation in governance can be attributed to a variety of reasons, but in general, they're looking to increase their value through discussions and relationships with prominent researchers, or through the fact that they've contributed to the Ethereum network.

Although (Reputation-based) non-economic incentives may not be able to absorb as many diverse participants in a short period of time as economic incentives, they can be effective in attracting participants who are more aligned with the long-term vision of the protocol to voluntarily participate in governance. Furthermore, the number of participants may be less dynamic than with economic incentives, making governance more stable.

As a result, there are many attempts to identify organic users who have voluntarily contributed a lot within the protocol and score their reputation based on their activity history and entrust them with specific governance (e.g., PolygonID, Badges for Optimism's Citizen House, etc.). This will require identifying participants based on various on-chain activities or account information, which can be accomplished by utilizing solutions that aggregate all on-chain data to provide per-account reputation scoring (e.g., Sismo, Cred Protocol, Orange Protocol, etc.), or by utilizing authentication badging such as Proof of Participation to prove specific activities, such as POAP.

The problem with this approach, however, is that it is inherently subjective to the entity scoring the reputation. (Eliza Oak of a16z categorizes reputation measurement methodologies into three main categories in her article: 1) Automated behavioral metrics, 2) Peer attestations, or 3) Centralized selection).

In short, there are both economic and non-economic ways to incentivize the right participants in governance, both of which have distinct advantages and disadvantages, and protocols will need to set the tradeoffs well for the outcomes they want to achieve through governance. A combination of economic and non-economic incentives can also be a good option - indeed, Optimism separates the areas of governance for the token-based Token House community from the reputation-based Citizen House community. Alternatively, it may be worthwhile to discuss a ‘Dual Governance’ model, such as the one the Lido team is discussing, to offset the limitations of token-based governance: establishing a separate governance organization for stETH token holders to serve as a check on the power of a single token (i.e., LDO).

Even if the protocol has onboarded a diverse set of right participants, it's unlikely that they will continue to be engaged if the proper governance process is not properly supported. For example, participation in governance can suffer if too many agenda items are proposed, or if it requires too much effort for participants to actually participate in governance.

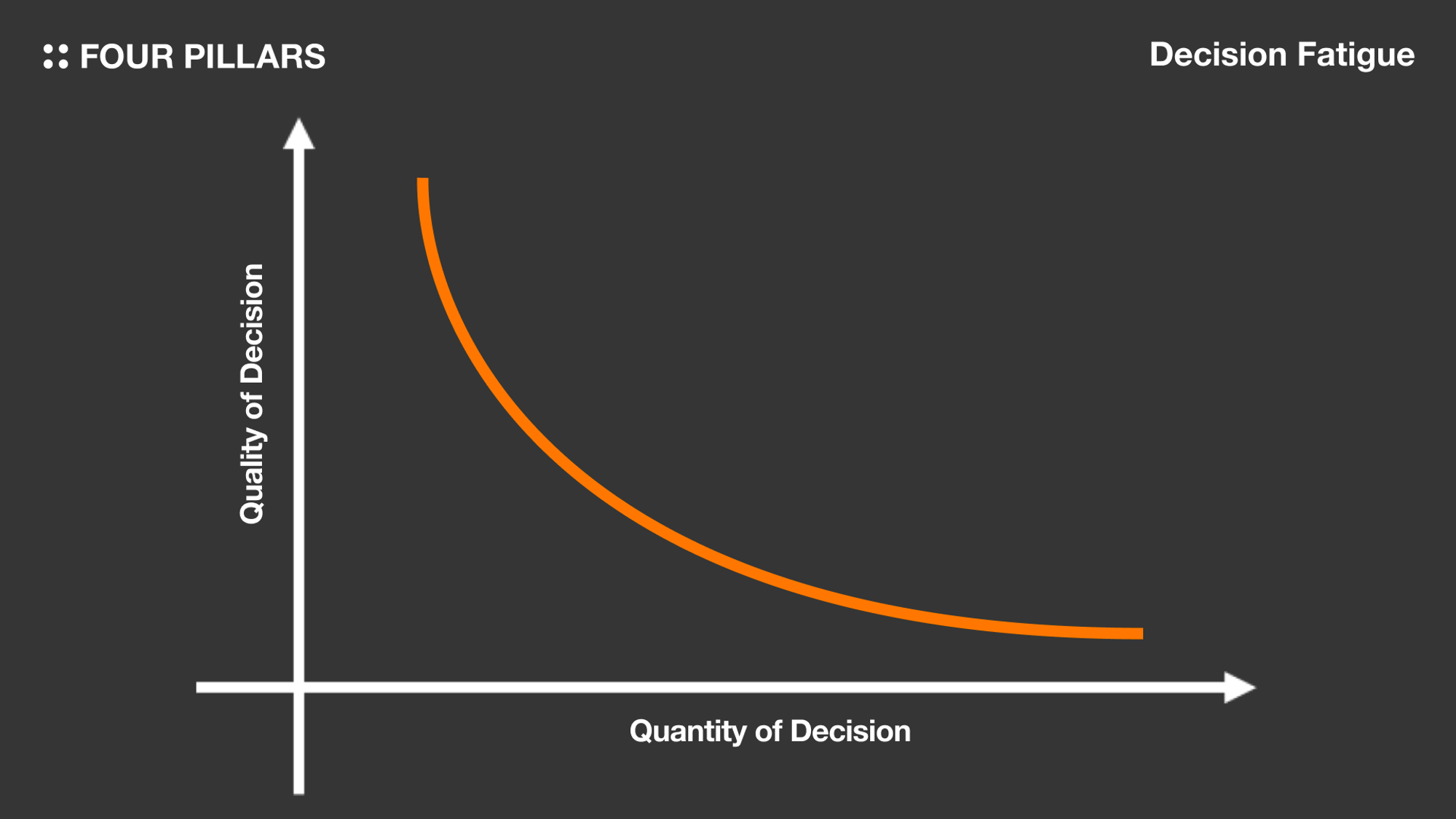

This is where ‘Decision Fatigue’ becomes an essential consideration.

Decision fatigue, a social psychology term, refers to the phenomenon that when people make frequent decisions, the quality of their subsequent decisions decreases. We can easily observe this phenomenon in our daily lives: on days when we have a lot to think about or make a decision, we sometimes get tired and find it harder to make a new decision, so we make a quick decision or even postpone it.

Even in the current blockchain governance space, the quality of decisions is often compromised by the large or irregular number of proposed agendas, as it is often easy for a wide range of participants to participate. Furthermore, since most of the important elements of the protocol are in code, there may always be an urgent agenda item* related to the risks associated with them. This is also one of the main contributors to decision fatigue, as it puts pressure on participants to keep track of every governance agenda item that is proposed on the protocol, regardless of its importance.

In addition, there are many other factors that can directly or indirectly contribute to decision fatigue because of the extra effort required to find the information to make a decision. For example, individual agendas may not be published with all the information needed to make a decision, or it may be necessary to know the context of other existing agendas. When this happens, if the protocol has fragmented communication channels for discussions, and lacks tools to look back on past governance discussions, existing participants can become fatigued to stay engaged - this also makes it difficult for new participants to join.

Moreover, decision-making systems that do not take into account the diverse geographical and linguistic distribution of participants make it difficult to communicate smoothly and unifiedly, and governance infrastructures that are actually related to processes such as communication and voting are often still adopting uncomfortable UX/UI. This overall lack of accessibility for participants to participate in governance is also one of the most important issues that needs to be improved, as it increases participants' fatigue and hinders active participation.

In short, as protocols can easily involve so many participants, it is essential to pay attention to how individual governance agendas are curated to ensure their continued engagement, and to actively utilize a variety of tools to mitigate decision fatigue, including enhancing the discussion process for agendas, adopting flexible frameworks based on governance scope, governance automation for recurring agendas, introducing landscapes to showcase governance history, etc.

*It is also a good idea to organize a separate emergency framework, such as Osmosis’ Expedited Module or Curve Finance’s Emergency DAO, especially for on-chain governance that is relatively inflexible compared to off-chain governance.

The judgment on 'whether a system that anyone can trust must be neutral' should be made by considering the purpose of the system, the kind of information used, and the impact of the system. However, in general, systems that aim to be decentralized should be neutral. As we've seen, the essence of decentralization is to meet the needs of diverse participants and to ensure that the system is consistently trusted, which requires it to be fair and objective to everyone.

To put this in the context of governance systems, the framework itself must be designed to be neutral so as not to favor any particular entity, but the consequences of individual agendas must also not undermine the neutrality of the system.

Below are some of the cases where the rights of certain parties have been compromised, raising awareness within the industry and beyond about the importance of neutral design of decentralized systems.

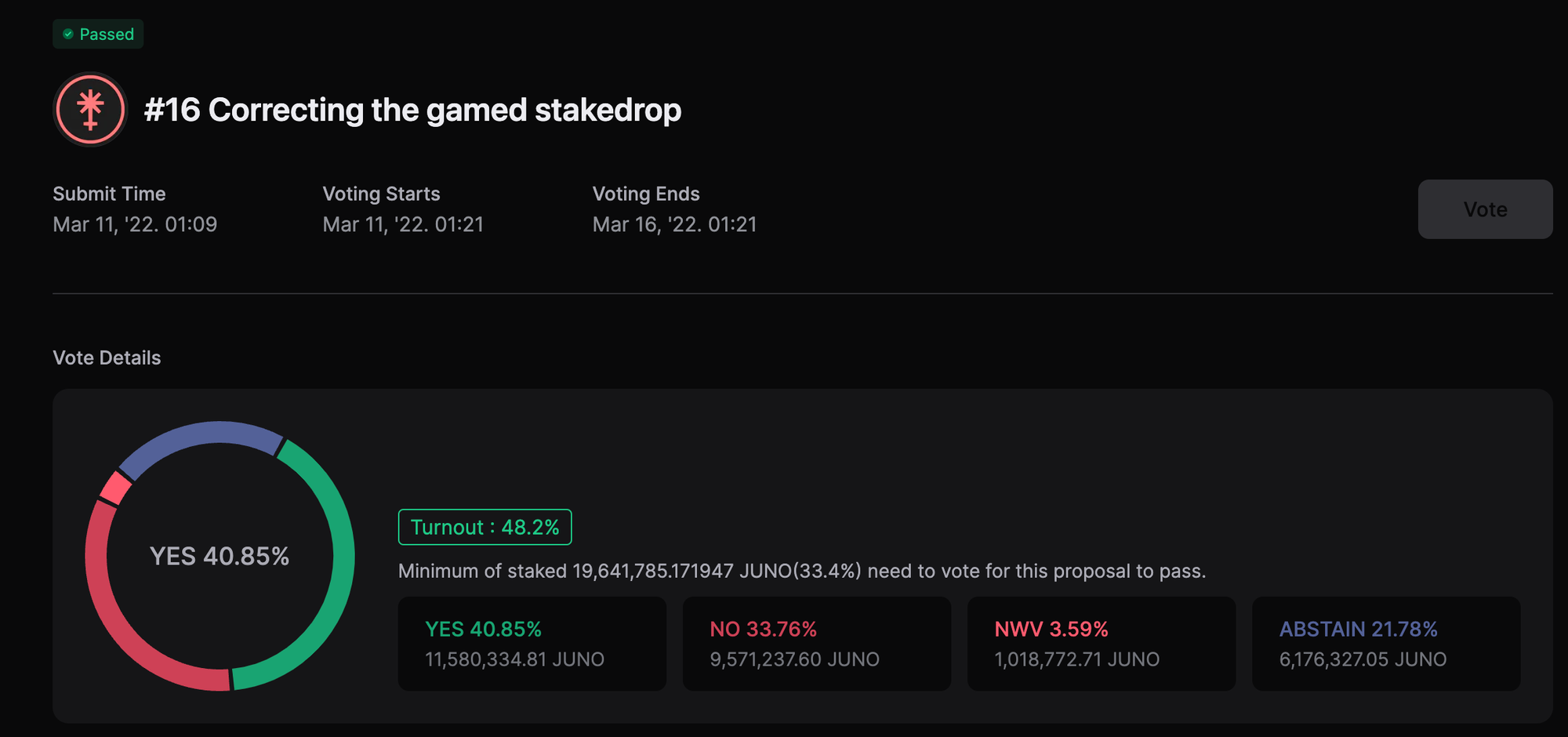

Juno Proposal #4, #16

Source : Keplr Dashboard

At launch, the Juno protocol distributed JUNO tokens via an airdrop to ATOM token stakers. The maximum amount of JUNO per wallet was capped at 50,000, but one player split and staked his ATOM across multiple wallets, receiving approximately 7% of the total JUNO airdrop.

This led to a proposal by the Juno protocol and community to confiscate the player's funds. The proponents argued that the player's actions undermined the decentralization of the JUNO ecosystem, while the opponents argued that the system design was flawed in the first place and that it was unfair to blame one player's actions and violate his property rights. The heated debate ultimately resulted in the proposal being passed by a narrow margin, and the player's funds were confiscated.

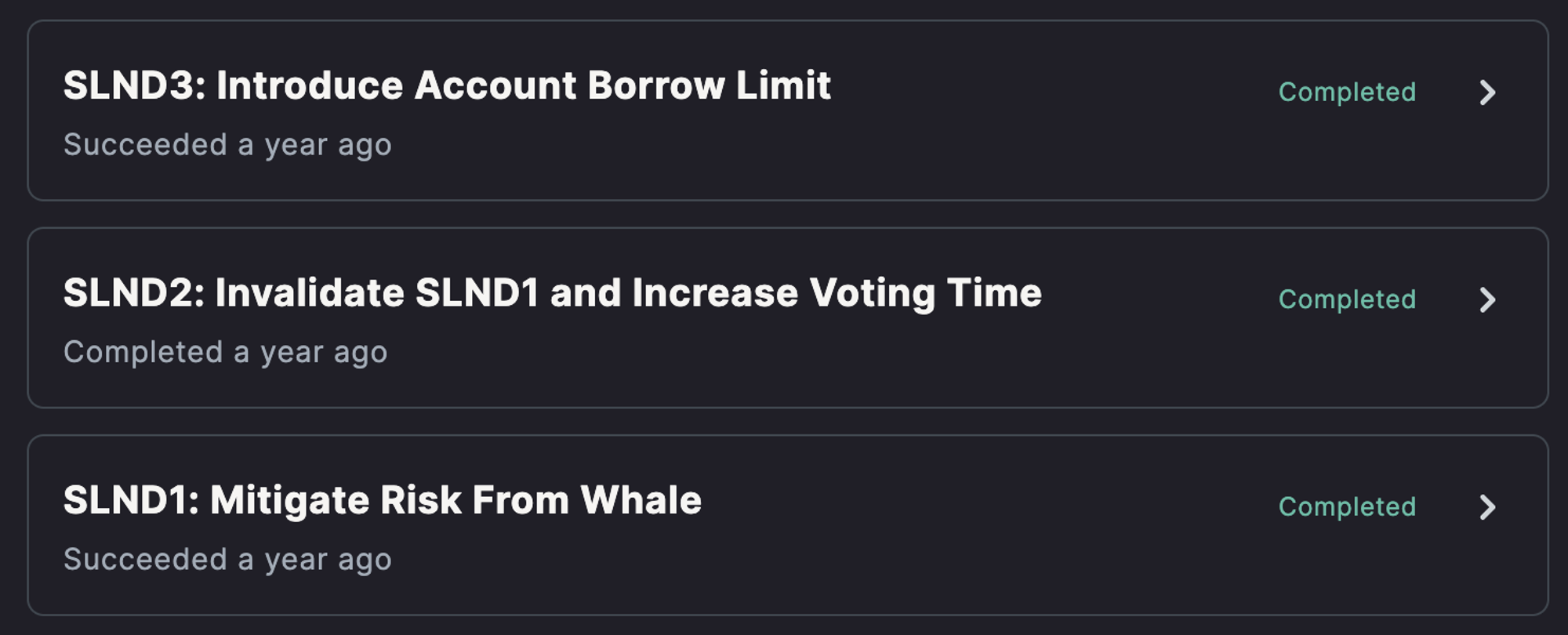

Solend Proposal #1, #2, #3

Source : Realms

On June 20, 2022, Solend, a lending protocol based on the Solana chain, posted its first proposal (SLND #1), which was somewhat outlandish - concerned about the plummeting price of SOL tokens in the event of a liquidation scenario from a single customer, which accounts for the majority of all deposits in Solend, the proposal was to 1) institute special margin requirements in the protocol and 2) temporarily revoke the authority of the customer's account so that its position could be liquidated first via OTC trade. The proposal passed with an overwhelming 97.5% approval rate.

However, following criticism that the voting period for the proposal was too short and violated customers' personal rights, the Solend team subsequently proposed a second and third governance proposal (SLND #2 & #3) to override SLND #1 and temporarily adjust the per-account borrowing limit, liquidation cutoff factor, and liquidation penalty. These proposals passed with over 99% support, and as a result, the liquidation that the community feared did not occur.

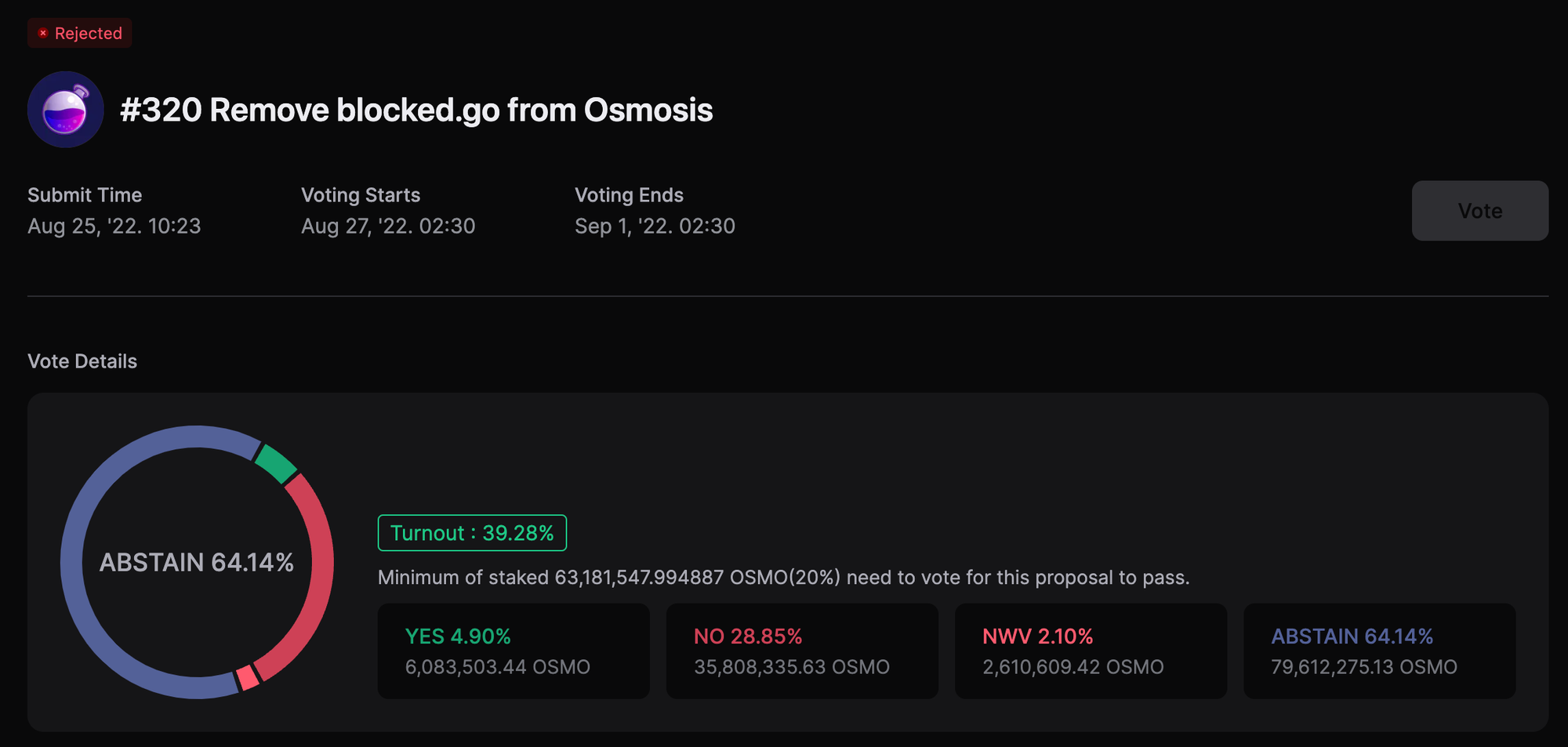

Osmosis Proposal #320

Source : Keplr Dashboard

In its 320th governance proposal, one member in Osmosis community proposes the removal of the Blocked.go file, which has always been included with every new update to Osmosis. The file contains 68 Ethereum addresses with a history of using Tornado Cash, and its continued existence could potentially subject the owners of the addresses in the file to restrictions by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).

The opponents of the proposal argued that the files should not be removed because they shared OFAC's sanctioning objectives of preventing money laundering and terrorist financing, while the proponents argued that blockchains are inherently censorship-resistant networks, and that accommodating censorship was unacceptable within the industry. In the end, the proposal was rejected with only 4.9% of the total voters agreeing, and as a result, Osmosis has continued to include this file in its all new updates.

These three cases have violated participants’ property rights in the protocols they were using, constrained their activity to maximize their gains, and caused them to fear that they may no longer be able to use the protocols because of certain past activities. Will participants want to continue to use these protocols?

If a system that is supposed to guarantee unlimited autonomy and accountability violates the rights of certain individuals, it will not be a system that can be trusted by anyone because the free participation of the majority is not guaranteed, and therefore it can never be said to be decentralized. Another point to consider is that the system should design the governance well in advance so that disputes within the community do not arise as a result of such controversies, and the responsibility should be placed on the system that did not pay attention in advance, not on the individual.

As decentralized systems become more advanced and the mention of related services accelerates, so does the interest in the potential use cases for decentralized governance. In response, methodologies for achieving decentralized governance are becoming increasingly diverse, and communities are experimenting with and breaking their own methodologies and learning from each other's use cases.

Of course, as mentioned earlier, governance is present in all areas of our lives, and there will never be one ultimate framework that can abstract all these cases. Nevertheless, decentralized governance is a methodology that reflects the distinct characteristics of blockchain that no one else has been able to apply, and it may be an approporiate form of governance in certain areas.

However, in order for these experiments to be more efficient and effective, it's important to at least understand the nature of decentralization and structure governance frameworks accordingly. It's also important to keep in mind that the primary purpose of governance is always to achieve organizational goals, so it can be very dangerous to get caught up in the consequential properties of a blockchain and get distracted by decentralized assortment. If we continue to experiment with governance without being fully aware of this, we may end up causing great harm to individuals or protocols without making any progress, which could have a negative impact on the development of decentralized governance and the blockchain industry itself in further.

It's also worth noting that protocols shouldn't be expected to build a decentralized governance framework out of the box. Today's stable democratic societies took hundreds of years or more to develop, with countless improvements along the way. Even if the blockchain industry itself ultimately fails to gain widespread adoption and interest in decentralization wanes, the records of the economies and cultures created within the communities that have developed through decentralized governance will remain a valuable record, with lessons for governance in the real world.

I hope this article serves as a meaningful resource for effectively experimenting with different decentralized governance frameworks.

Thanks to Kate for designing the graphics for this article.

We produce in-depth blockchain research articles

The crypto industry, initiated by Bitcoin, has developed through the narrative game and is now entering a stage where its technical infrastructure is maturing. Crypto provides a foundation to assign economic value to any idea or interest and enables trading, paving the way for new types of applications and business models. Currently, the crypto industry faces the key challenge of developing popular applications and attracting users. To achieve this, it is necessary to actively apply strategies that leverage speculative demand as a core function.

This article is the last part of a three-part series covering the DeFerence 2024 event, sponsored by Four Pillars.

Base, aiming to onboard 1B onchain users, has emerged as a hub for consumer-oriented onchain applications within a year since its mainnet launch last year, driven by factors such as reduced fees, the memecoin frenzt, and the growth of social network applications like Farcaster. Unlike other blockchain ecosystems focused on DeFi and infrastructure, Base predominantly features consumer-oriented applications similar to Web2 services. It leverages a unique community and brand to onboard more applications. While social and community applications are the most actively developed, new categories of onchain applications in content, gaming, and commerce are also emerging, indicating significant potential for user expansion.

This article is the second part of a three-part series covering the DeFerence 2024 event, sponsored by Four Pillars.